Trilingually Tongue-Tied

My whole life, I’ve been asked the same question: “What’s your background?”

I get it. I look mixed. I am mixed.

My answer is always the same: “My mom is Vietnamese and my dad is Iraqi.” I rarely say that I’m Vietnamese-Iraqi (even though I am) because the truth is, I don’t feel like either one of them. They’re just parts of a whole.

I’m an only child with immigrant parents from two different countries, two different cultures, and two different languages. I was born in Canada, and the only time I was fluent in my parents’ languages was when I was a kid. As I got older, I stopped speaking them out of embarrassment or laziness, and now I only know parts of the languages. My mom and her family speak to me in Vietnamese, and I understand most of the simple sentences, but I stumble over my own tongue trying to conjure up a sentence in response. It’s clear in my head, but the second it leaves my mouth, I sound like a Canadianized broken record. I’m even worse with my dad’s language—the extent of my Arabic speaking ability stops at a handful of words and counting from one to ten.

My parents don’t speak each other’s languages either. As you can imagine, Vietnamese and Arabic aren’t even remotely similar, so we all speak English to each other. We’re a family of three who lives in a trilingual household, though none of us are truly trilingual. Maybe we’re bilingual at best. But I can’t even claim that term because I’m only fluent in one language, and that’s English. Speaking English has always been easier for me. I hear it on TV, I speak it at school and with my friends, and it’s how I communicate with my parents. English is an overpowering language, but it’s one that I have control over, and it’s what I understand the most.

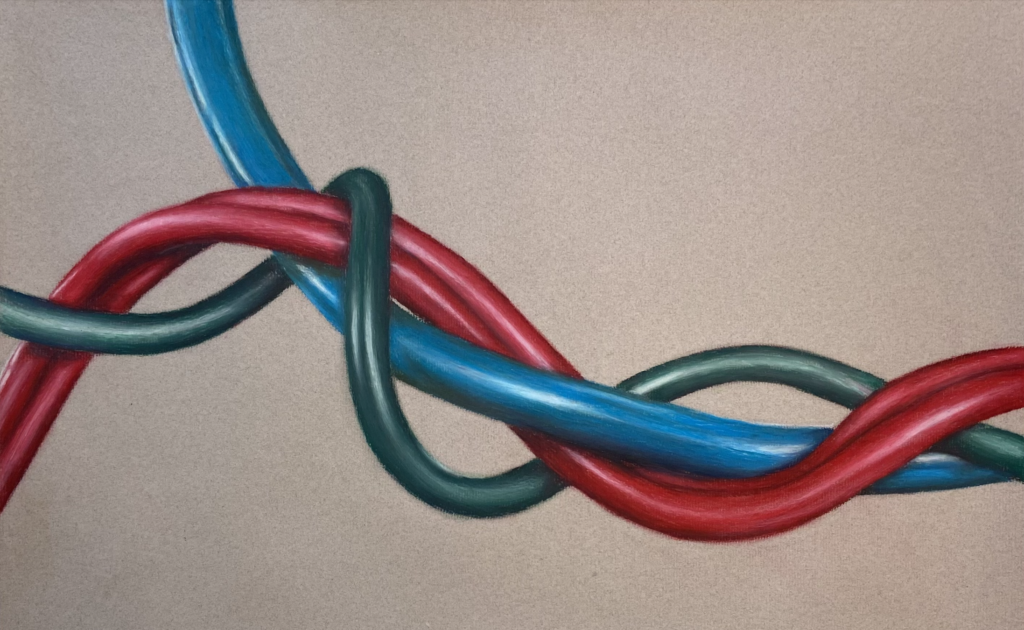

With that said, I think language is noise that has meaning. But meaning can only go so far when you don’t understand much of the language. That’s when noise takes over. Now you’re left with this tangle of clashing accents like a DJ trying to mash together two songs that don’t quite fit.

The high and low waves of Vietnamese contrasting with the throaty thickness of Arabic is a jumbled soundtrack that has seeped into my ears for the past 22 years. It plays when my parents are on the phone with relatives and when we have family gatherings. Sometimes the noise is easy to tune out—just like voices on the TV or the hum of the refrigerator. Other times, it’s all I hear, and I’m stuck between walls of frustration and curiosity. I want to understand. But I can’t just click a button and turn on the subtitles like I’m watching something on Netflix.

Let me paint a picture for you. It’s Christmas Eve, and my dad’s side of the family is gathered around our dining table. Everyone’s throwing their heads back, laughter echoing through the house, and I’m sitting there staring at my plate and willing my ears to grasp at even the slightest familiar Arabic word or sound. I resist the urge to pull out my phone and tune out the noise, forcing my lips into a smile so it looks like I’m enjoying myself. But the blankness behind my eyes—the confusion—is a dead giveaway. I don’t want to ruin the moment and ask, What are you talking about? Instead, I sit there quietly until I catch my dad’s eye and he says, “Oh, we have to translate.”

I’m better with Vietnamese, but not by much. My mom speaks to me in her language and I reply in English. How ridiculous. I feel embarrassed when I walk past a kid on the street confidently speaking to their parents in their first language, remembering when I had the same skill at their age and wishing I stuck with it. Now I’m just stuck. My ears perk up when I hear people speaking Vietnamese in public; I can pick up on a few phrases, but my tongue is still useless. My mind echoes with my mom’s voice urging me to speak her language: Nói tiếng Việt, đi. I never listened. I always cringe at the sound of my voice trying to speak Vietnamese. It just doesn’t sound right, and even the slightest slip in pronunciation can mean something entirely different from what I intended.

I have a cousin who lives in the States, only two years younger than I am, and she’s fluent in both Vietnamese and English. She was born in Vietnam, though, and both her parents are Vietnamese. She’s exposed to the language every day. She uses it every day. I can’t help but wonder, would I be fluent too, if I was born there and not in Canada? Would I be fluent if I wasn’t mixed? I feel substandard; I’m not Vietnamese enough.

My mom often tells this story: I visited the homeland with her when I was two and a half years old and spoke Vietnamese exclusively. When I got back to Canada, I spoke Vietnamese to my dad like it was second nature. “I don’t know what you’re saying!” he said. I was horrified. After that, I dropped the language entirely and clung to English like a life raft so that I would be understood.

What now? Two decades later, I’m still striving to be understood. To understand. The current of syllables is too loud and moves too fast, and I’m drowning in the syntax. There’s so much miscommunication and so much Missed Communication that I can’t get back.

You speak

nói chuyện

I don’t have all the pieces

to complete the puzzle

I am constantly playing a game

of broken telephone

không hiểu tiếng

You wish I’d talk to you more but I stutter

in your native language; every syllable

foreign to my stubborn tied tongue

muốn talk nhiều

mà không speak được

We look alike but can’t see

each other

based on surface-level conversation

không thấy

I utter a few words on FaceTime

because it’s all I can muster

hello, khỏe không?

Mother, I’m xin lỗi

for losing your tiếng

I hope you know that I thương you

I can get away with mixing English and Vietnamese when I speak to my relatives in the States. My family in Vietnam, on the other hand, doesn’t know much more than “Hello.” I have no choice but to butcher the language. I take the easy route and speak using the most simple sentences possible. The problem is that a lot of detail is left out when I do that. I speak like I’m in the first grade. There’s no flair in my words. Sometimes I even have to say the same phrase more than once before my family understands, and the more I repeat myself, the more foreign the words sound to me, like how a word starts to lose meaning when you say it over and over or stare at it for too long. My own voice starts to sound foreign.

The language is like an incomplete jigsaw puzzle in my brain; there’s enough there to see the bigger picture, but some of the smaller parts are missing. All I have are fragments. I twist my tongue into knots trying to pronounce each syllable, trying to find the words and form them into sentences as if they’re the puzzle pieces that I have to put together.

The last time I visited Vietnam was in 2017. I was in a taxi with my aunt, and my basic Vietnamese sentences weren’t enough, so she pulled up Google Translate. We resorted to typing sentences in our respective languages, swapping her phone every couple of minutes; we were having a conversation without speaking. If you’ve ever tried to translate full sentences on Google, you’d know that it doesn’t really work. Again, there’s enough to make out the bigger picture, but some of the detail and the nuances are distorted. Still, it was better than nothing. I tried reading the Vietnamese sentences she wrote and sounded out the words in my head as best as I could, matching their resemblance to the words I knew from hearing my mom speak. I wish I knew all of it but the bottom line was that I understood, to a certain extent.

I can’t do that with Arabic.

The language is nearly impossible to learn. At least with Vietnamese, the alphabet is almost the same as English but with a bunch of accents on the letters. Reading Arabic is like trying to read a doctor’s scribbles; it’s more pleasing to look at, but just as hard to understand. I can recognize some words when I hear them—like dog, car, tea, and milk—but there’s no way for me to match the sounds to the written language like with Vietnamese. On top of that, Arabic is read from right to left, which makes it all the more challenging to read.

tea = chai

milk = haliib

As I’m sitting cross-legged and hunched over on my bed writing this, I’m realizing just how much more connected I am to my mom’s language than my dad’s, even though the opposite is true in terms of which side of the family I see more often. I have some Iraqi relatives in Canada (in Ontario, actually), but the closest Vietnamese relatives to me are about a four-hour flight across the border. The rest are in a timezone 12 hours ahead.

Still, I’ve mentioned Vietnamese a lot more than I mentioned Arabic. And yet, I feel equally distant from both parts of my identity. My facial features already set me apart from my ethnicities, and I can’t compensate by speaking the languages, so how else do I fit in? How else can I connect to my heritages?

It’s complicated. I’m complicated. And I have complicated Concepts of Self.

my almond eyes give it away. is it less obvious if i wear my glasses? i tend to shape-shift throughout the day—my natural superpower.

what’s your background? it’s okay, i’m not offended. i’m a foreigner in my own family (maybe a tourist at best).

it’s usually more fun to make people guess. call it jeopardy. you get a point for every wrong country and i always win. i look nothing like what i’m supposed to be—an impostor.

i’m half-napalm, half-terrorist. aren’t two halves supposed to make a whole? it’s hard being the victim and the perpetrator. i’m a living juxtaposition; yin and yang.

am i still subject to asian fetishes if i don’t look fully asian? gaze all you want, anyway. i’ve learned to be an attention whore.

my mouth isn’t flexible enough; my throat’s not phlegmy enough. i speak broken native tongues. my shameful stuttering is a language of its own.

i stuff myself with ethnic foods in hopes that one day i’ll be full.

___

Response to Billy-Ray Belcourt’s This Wound Is a World

When I was a kid, my response to that burning question I mentioned in the beginning was, “I’m Canadian.” Even then, I recognized that I was different. That I didn’t fit into my cultures. I still feel that way now. My identity is made up of several fragments, and I’m still figuring out how to make them whole.

Identity starts with the letter I.

I am mixed. I am exotic. I am ashamed.

How can I claim to be a part of either side of my family when I barely know the languages? I’m stuck in the middle like a flag tied to a tug-of-war rope being pulled on both sides and not getting anywhere.

I think I might be more Canadian than anything else; but the thing is, I don’t want to be just Canadian. I like being mixed. I like making people guess my ethnicity, and then seeing their surprised and intrigued reactions when I finally tell them what I am.

What if… I’m the rope itself?

My identity is just as twisted as my tongue when I try to speak my parents’ languages, but whether I know the languages or not, they’re within me—in one way or another. Language is complicated, but so am I. Each thread represents a part of me, woven together like the spirals of my DNA. The rope can get knotted, or it can unravel, but the threads will always be there.

That’s the thing about noise, too. It’ll be there even though I don’t understand all of it, and it’ll carry on even if I tune it out. I’ve come to realize that I prefer noise over silence. The best I can do is try to listen, and if I try hard enough, maybe eventually I’ll get to the meaning.

AMANDA NAOUM is in her fourth and final year of the Professional Writing and Creative Writing programs at York University. She specializes in drawing and painting realistic portraits; you can find Amanda working on commissions or binge-watching shows on Netflix in her free time. Metanoia is Amanda’s first time as a PWSA Symposium panelist.